Oil - The political economy of foreign oil policy

Oil has been unique as a vital resource owing to its pervasiveness in the civilian economy and its continuing centrality to military power, and maintaining access to the great oil-producing areas of the world has been a key goal of U.S. foreign policy since World War I. The objective of maintaining access to economically vital overseas areas resonated with the global conception of U.S. national security interests that emerged during World War II and dominated U.S. policy throughout the Cold War. U.S. leaders sought to prevent any power or coalition of powers from dominating Europe and/or Asia, to maintain U.S. strategic supremacy, to fashion an international economic environment open to U.S. trade and investment, and to maintain the integration of the Third World in the world economy.

Control of oil helped the United States contain the Soviet Union, end destructive political, economic, and military competition among the core capitalist states, mitigate class conflict within the capitalist core by promoting economic growth, and retain access to the raw materials, markets, and labor of the periphery in an era of decolonization and national liberation. Moreover, the strategic forces necessary for maintaining access to overseas oil were fungible; that is, they could, and were, used for other purposes in other parts of the world. Likewise, as the Gulf War demonstrated, strategic forces from other parts of the world could be used to help maintain access to oil. Thus, there has been a symbiotic relationship between maintaining power projection capabilities in general and relying on strategic forces to maintain access to overseas oil. In short, control of oil has been a key component of American hegemony.

While national security concerns have been an important source of foreign oil policy, definitions of national security and national interest have not been shaped in isolation from the nature of the society they were designed to defend. Arguments that claim a noncapitalist United States would have followed the same policies, even when sincere, assume no changes in domestic economic, social, and political structures, and thus miss the point entirely. They also ignore the constraints, opportunities, and contradictions that the structure of society, and in particular the operation of the economic system, impose on public policy.

The expansion of U.S. business abroad beginning in the late nineteenth century increasingly linked the health and survival of the U.S. political economy to developments abroad. These concerns were not restricted to fears for the nation's physical security or to the well-being of specific companies or sectors but rather were linked to concerns about the survival of a broadly defined "American way of life" in what was seen as an increasingly dangerous and hostile world.

U.S. oil companies were among the pioneers in foreign involvement, looking abroad initially for markets and increasingly for sources of oil. The U.S. government facilitated this expansion by insisting on the Open Door policy of equal opportunity for U.S. companies. Although the United States became a net importer of oil in the late 1940s, it was able to meet its oil needs from domestic resources until the late 1960s. Still, U.S. leaders were aware as early as World War II that one day the nation would no longer be able to supply its growing consumption from domestic oil production. This realization led to a determination to maintain access to the great producing areas abroad, especially in the Middle East.

Once the issue was defined in terms of access to additional oil, the interests of the major oil companies, which possessed the means to discover, develop, and deliver this oil, coincided with the national interest. In these circumstances, the major international oil companies have been vehicles of the national interest in foreign oil, not just another interest group. To maintain an international environment in which private corporations could operate with security and profit, the U.S. government became actively involved in maintaining the stability and pro-Western orientation of the Middle East, in containing economic nationalism, and in supporting private arrangements for controlling the world's oil.

Although there was a broad consensus in favor of policies aimed at ensuring U.S. control of world oil, the structure of the U.S. oil industry significantly shaped specific struggles over foreign oil policy. Like much of U.S. industry, the oil industry was divided between a mass of small-and medium-sized companies and a handful of large multinational firms. Within these divisions the competing strategies of different firms often led to intense conflict and to efforts to enlist government agencies as allies in the competitive struggle. Any public policy that seemed to favor one group of companies was certain to be opposed by the rest of the industry. Divisions within the industry were at the base of much of the oil companies' ideological opposition to government involvement in oil matters. In addition, oil companies shared the general distrust of the democratic state that prevailed throughout American business.

There were also conflicts with other energy producers, especially the coal industry, though these were somewhat muted owing to oil's near monopoly position in the transportation sector. Coal, in contrast, was used mainly for heating and electricity generation, as was natural gas, which increased its share of overall U.S. energy consumption, largely at the expense of coal. There was less conflict with industries that were themselves heavy oil users, in part because most of them were able to pass increased costs along to consumers. The automobile industry, in particular, has been heavily dependent on inexpensive oil for its very existence, and thus has shared the oil industry's interest in continued and growing use of its products.

The U.S. government was also frequently divided over foreign oil policy. Competing bureaucracies and institutions, each with their own set of organizational interests, supported different policies. While these divisions often influenced the specific contours of foreign oil policy, they generally reflected the divisions in the U.S. oil industry. For both organizational and ideological reasons, the Department of State has represented the interests of the major oil companies whose actions can have a great impact on U.S. foreign policy. Congress, in contrast, has played its traditional role as the protector of small business and often backed the numerically dominant independent oil companies and the coal industry, whose interests have been mostly within the United States. Presidents have tried to mediate the conflicts among government agencies, with Congress, and among competing industry groups, and craft compromises acceptable to the greatest number of groups possible.

Even though industry and government divisions effectively blocked some types of government actions, the splits did not reduce the oil industry's influence on U.S. foreign policy. Almost all segments of the oil industry agreed on policies aimed at creating and maintaining an international environment in which all U.S. companies could operate with security and profit. Thus, the impact of business conflict was not a free hand for government agencies but rather strict limits on government actions and control of the world oil economy by the most powerful private interests.

Foreign oil policy has been shaped not only by the structure of the oil industry, which has changed over time, but also by the privileged position of business in the United States. The oil industry has operated in a political culture that favored private interests and put significant limits on public policy. Thus, the fact that business interests were often divided and that specific business interests at times did not prevail does not mean, as some analysts argue, that the oil industry and other business sectors had little influence on U.S. foreign policy. On the contrary, the overall structure of power within the United States had a profound impact on U.S. foreign oil policy.

Corporate power not only influenced the outcome of specific decisions but more importantly, significantly shaped the definitions of policy objectives. The realization that U.S. oil consumption threatened to outpace domestic production led to plans to ensure access to foreign oil reserves. The alternative of reducing, or at least slowing, the growth of rapidly rising consumption has only rarely been seriously considered.

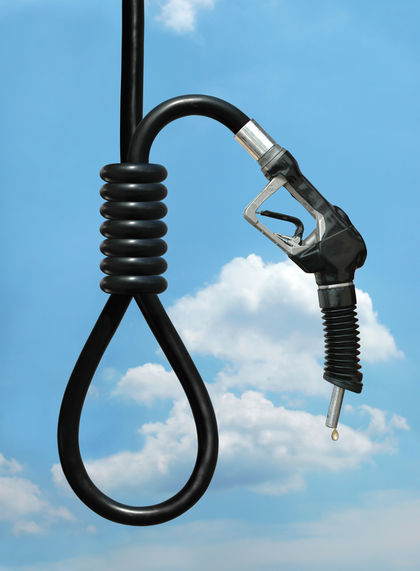

Part of the reason for a supply side focus has been the obvious strategic and economic advantages of controlling world oil. Nevertheless, the degree to which U.S. public policy has ignored conservation cannot be explained solely by foreign policy considerations. The consideration and adoption of alternative policies limiting the consumption of oil has also clashed with well-organized political and economic interests, deep-seated ideological beliefs, and the structural weight of an economic system in which almost all investment decisions are in private hands.

The oil industry has been one of the most modern and best-organized sectors of the U.S. economy, and both domestic and international companies have opposed policies that reduce the demand for their products. Domestic producers have argued that greater incentives for domestic production are the answer to U.S. oil needs, while companies with interests overseas have argued that they can supply U.S. oil needs, provided they receive government protection and support.

Demand-side planning, in contrast, involves end-use and other restrictions that clash with the interests of the oil industry and other industries using oil. Planning for publicly defined purposes, such as limiting demand for oil products, requires a role for public authority—supplanting the market in some areas—that has been unacceptable to the dominant political culture of the United States. In addition, the patterns of social and economic organization, in particular the availability of inexpensive private automobiles, the consequent deterioration of public transportation, and the continuing trend toward increased suburbanization, all of which were premised upon high oil consumption, have been regarded as natural economic processes not subject to conscious control, rather than as the results of identifiable, and reversible, social, economic, and political decisions. Conservation also goes against the ideology of growth and the desire, reinforced by the experiences of depression and war, to escape redistributionist conflicts by expanding production and the absolute size of the economic "pie." Finally, decisions to look to external expansion to solve internal problems rather than confront them directly has been characteristic of U.S. foreign policy throughout the nation's existence.

The structure of power within the United States has also deeply affected the U.S. response to the environmental impact of oil use. While abundant oil has helped fuel American power and prosperity, it also helped entrench social and economic patterns dependent on ever-higher levels of energy use. Whether or not these patterns are sustainable on the basis of world oil resources, it has become increasingly clear that they are not sustainable ecologically, either for the United States or as a model of development for the rest of the world.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, oil accounted for 40 percent of world energy demand, and energy use was the primary source of carbon dioxide, the main greenhouse gas. For this reason, environmental scientists considered air pollution associated with energy use to be the main threat to the earth's climate. Increased energy demand will only make the situation worse. In short, there are environmental limits to continuing, let alone expanding, the high production–high consumption lifestyle associated with the U.S. model of development. Therefore, the most important question facing the United States in regard to oil in the twenty-first century may not be how to ensure access to oil to meet growing demands, but rather how to move away from what is clearly an unsustainable development path.

Comment about this article, ask questions, or add new information about this topic: